Sports can be like a cold war between ‘rival’ countries, that is against the sports spirit. Football, often recognized as a dramatic game that elicits intense emotions, an equal combination of sport and theatre, but can a football match ever start an actual war? Let’s find out

Introduction

This international conflict and war took place between two Central American nations, namely- El Salvador and Honduras. In the 1960s both these countries were under military dictatorship under Salvadoran General Fidel Sánchez Hernández and Honduras President Oswaldo López Arellano.

The Republic of El Salvador with an area of 21,041 sq. km was accommodating a population of 36 lakh approximately by 1969 whereas Honduras with an area of 1,12,492 sq. km was home to just 26 lakh people. Most of the large Salvadoran population was made up of farmers who didn’t have enough land to live and work on so they started migrating to Honduras through the shared border.

Relationship

By 1969 more than 300,000 Salvadorans were living in Honduras. These Salvadorans made up 20% of the population of Honduras. In Honduras, as in much of Central America, a large majority of the land was owned by large landowners or big corporations. The United Fruit Company owned 10% of the land, making it hard for the average landowner to compete. In 1966 United Fruit banded together with many other large companies to create la Federación Nacional de Agricultores y Ganaderos de Honduras (FENAGH; the National Federation of Farmers and Livestock-Farmers of Honduras). FENAGH was anti-peasantry (against the Campesino) as well as anti-Salvadoran. This group put pressure on the Honduran president, General Arellano, to protect the property rights of wealthy landowners In 1962 Honduras successfully enacted a new land reform law.

Fully enforced by 1967, this law gave the central government and municipalities much of the land occupied illegally by Salvadoran immigrants and redistributed it to native-born Hondurans as specified by the Land Reform Law. The land was taken from both immigrant farmers and squatters regardless of their claims to ownership or immigration status.

This created problems for Salvadorans and Hondurans who were married. Thousands of Salvadoran labourers were expelled from Honduras, including both migrant workers and longer-term settlers. This general rise in tensions ultimately led to a military conflict.

FIFA Qualifiers, 1969

In June 1969, Honduras and El Salvador met in a two-leg 1970 FIFA World Cup qualifier.

There was fighting between fans at the first game in the Honduran capital of Tegucigalpa on 8 June 1969, in which Honduras won 1–0 as the away team wasn’t allowed by the citizens to sleep at night due to the immense disturbance.

The second game, on 15 June 1969 in the Salvadoran capital of San Salvador, was won 3–0 by El Salvador before which the Honduras team was met with the same disturbing behaviour and to add fuel to the fire instead of the Honduras flag a white dirty rag was raised by the Salvadorians. Reportedly the Salvadorian coach told the players that they were lucky they had lost while going back in a bulletproof bus victimized by the Honduras stone-pelting throughout the way.

On 27 June, the deciding match of who would make it to the world cup was held. El Salvador emerged out victorious, with an extra-time goal. This incited violence and riots among the fans present in the country as well as in both nations. Warlike sports serve to discharge accumulated aggressive tension and therefore act as alternative channels to war, making it less likely.

The 100 Hours War

Late in the afternoon of 14 July 1969, the concerted military action began. El Salvador was put on a blackout and the Salvadoran Air Force, using passenger aeroplanes with explosives strapped to their sides as bombers, attacked targets inside Honduras. Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza Debayle helped Honduras by providing weapons and ammunition.Initially, rapid progress was made by the Salvadoran army within striking distance of the Honduran capital Tegucigalpa.

The momentum of the advance did not last, however. The Honduran air force reacted by striking the Salvadoran Ilopango air base. Honduran bombers attacked for the first time in the morning of 16 July. When the bombs began to fall, Salvadoran anti-air artillery started firing, repelling some of the bombers. The bombers had orders to attack the Acajutla Port, where the main oil facilities of El Salvador were based. Honduran air-raid targets also included minor oil facilities such as the ones in Cutuco. By the evening of 16 July, huge pillars of smoke arose in the Salvadoran coastline from the burning oil depots that had been bombed. By the time the Organization of American States managed to arrange a ceasefire on 18 July, it was thought about 3,000 people had died.

El Salvador finally withdrew its troops on 2 August 1969. On that date, Honduras guaranteed Salvadoran President Fidel Sánchez Hernández that the Honduran government would provide adequate safety for the Salvadorans still living in Honduras. Sánchez had also asked that reparations be paid to the Salvadoran citizens as well, but that was never accepted by Hondurans. There were also heavy pressures from the OAS and the debilitating repercussions that would take place if El Salvador continued to resist withdrawing its troops from Honduras. Trade ceased between both nations for decades and the border was closed. The war went on for about 4 days, hence the alternative name.

Aftermath

El Salvador was eliminated from the World Cup after losing their first three matches.

El Salvador suffered about 900 mostly civilian deaths. Honduras lost 250 combat troops and over 2,000 civilians during the four-day war. Most of the war was fought on Honduran soil and thousands more were made homeless. Trade between Honduras and El Salvador had been greatly disrupted, and the border officially closed. This damaged the economies of these nations tremendously and threatened the Central American Common Market (CACM). The war resulted in a 22-year suspension of the CACM, the political power of the military in both countries was reinforced, the social situation in El Salvador worsened, as the government proved unable to satisfy the economic needs of its citizens deported from Honduras.

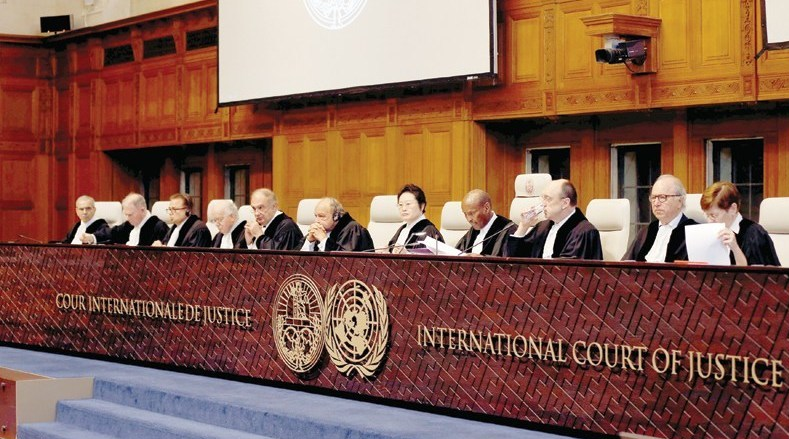

The resulting social unrest was one of the causes of the Salvadoran Civil War, which followed approximately a decade later. 11 years after the war the two nations signed a peace treaty in Lima, Peru on 30 October 1980 and agreed to resolve the border dispute over the Gulf of Fonseca and five sections of the land boundary through the International Court of Justice (ICJ). In 1992, the Court awarded most of the disputed territory to Honduras, and in 1998, Honduras and El Salvador signed a border demarcation treaty to implement the terms of the ICJ decree.

There are still tensions between El Salvador and Honduras. Border disputes between both sides continue to this day, despite an International Court of Justice (ICJ) ruling on the issue.

Conclusion

While it is easy to dismiss the war off as ‘childish’ and ‘passion-fueled’, it was capitalist greed that triggered the chain of events that, unfortunately, coincided with the FIFA qualifiers, causing the game to be politicized. Despite discord between the two countries, Pipo Rodriguez, the man who scored the fateful goal for El Salvador, says that it was not rancour that he remembered. "For me, that goal will always be a source of sporting pride. Neither from the Honduras players, nor from our side were the games between enemies, but were, between sports rivals," he said

~ Somya Maan

Comentarios